All About Amaranth, or Some Like it Everlastingly Hot: a short guide for planting, eating, bouqueting, and seed saving with this summer beauty

Amaranth (Amaranthus sp.) is a “cosmopolitan” plant genus with over 100 species, making it native across most of the world’s continents and endemic everywhere else save Antarctica. It is a highly nutritious plant: the seeds (referred to as a grain, or more accurately a “psuedograin” or “psuedocereal”) form a complete protein (the nine essential amino acids are present) and the leaves are vitamin dense. Amaranth’s nutritional potency is complemented by a flexible growing style (perhaps unsurprising given its global prevalence). Its adaptability to diverse soil types, fertilities, and watering regimes along with the prodigious seed output of certain strains make it an ideal subsistence food crop for home gardens and other small growing spaces. The Permaculture Research Institute has demonstrated amaranths are “dynamic accumulators,” which Dean Brown defines as plants that uptake “concentrations of useful nutrients (from the subsoil) into their biomass” which can then be used as mulch. Amaranths are also grown as cut flowers (“Amaranthus”); their bold colors, variegated foliage, and tall stature are aesthetic in the garden.

Amaranth is a significant food source to the Inca, Maya, and Aztec populations throughout Latin America. Throughout the 1500s the Catholic church’s conquistadors eradicated the crop as a strategy to colonize and subjugate the indigenous populations, violently quelling any attempts to grow it. Today Amaranth is embroiled in farmers' war on noxious / “invasive” weeds. A number of amaranth species threaten monoculture industrial crop production, particularly corn, cotton, and soy. Waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus) and Palmer’s Amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) are two of the most herbicide resistant plants in the world; the latter has evolved into a “superweed” as an unintended consequence of breeding glyphosate resistant GMO crops. These strains and others have now shown resistance for multiple herbicides including dicamba and 2,4D. There is a certain poetry to this, as the Greek etymology of the word “amaranth” means “unfading,” “everlasting,” and often interpreted as “immortal.”

Cultivation

Amaranths like it hot. The optimal soil temperature* for seed germination is 70-75F. Iin these conditions, seeds will germinate within 3-5 days. Seedlings grow rapidly, especially as daytime temperatures reach 90-100F and beyond. Seeds can also be planted in cooler temperatures, but expect longer germination times and slower growth.

Amaranth tends to resist predation from squirrels and other rodents. This makes direct seeding outdoors imminently practical: the quick growth and the bold colors of many strains make them easy to distinguish from weeds that would outpace other common vegetable plants. When seeding, cover with a thin layer of topsoil. Do not sow seeds too deep; the tiny diameter of amaranth seeds means they need very little coverage to sprout and begin photosynthesis.

Amaranth’s heat tolerance makes it a great seasonal substitute for other leafy greens such as kales, collards, and spinach, which all prefer far cooler temperatures. Amaranth leaves are harvestable within 20-30 days when seeded in ideal climate conditions. Lightly harvest leaves or densely sow plants and thin out entire plants as they grow. Use as a salad green, lightly braise on the frying pan or steam. As leaves mature they remain edible but become less palatable and more fibrous. And note that amaranth, spinach, chard, and beets are all related - meaning their leaves contain oxalates when raw, and should be avoided for those who are pursuing a low oxalate diet.

Amaranth is drought tolerant, but consistent waterings and fertility will improve yields and leaf flavor. Use wider plant spacings and deeper waterings if planting for grain production. Taller trunk types benefit from modest trellising but this is totally optional. The theme is flexibility.

While amaranth is heat tolerant, it is conversely not cold tolerant. Mid-summer seedings can still produce leafy greens but if you want grain / saved seed, plant as early as possible to maximize yields. Plants have a low frost tolerance and are considered hardy to Zones 10b (35°F - 40°F) and above.

Seed saving

Amaranth was the very first crop we saved seed from, in the halcyon days before Plant Good Seed was even a formal company. If you already feel inspired to grow amaranth, it provides an ideal gateway to the world of seed saving.

Harvest flowering heads when a “critical mass” of seeds are mature. Seed maturity can be determined in a multitude of ways. One tell is the presence of snacking birds. Alternatively, you can gently tap or shake flowering amaranth stalks into the palm of your hand and see if seeds fall out. Check sporadically as the season deepens, testing to see how much seed is dislodged, and make your own subjective call when the full plant is ready for harvest. At this point, cut flowering stalks with a pruner, leaving some stem material on the plants. This helps any remaining immature seed ripen. Leave the material to dry down in a plastic tub or bucket, which prevents seed loss.

Cleaning seed: Agitate fully dried material by hand in a plastic tub. Focus on the flowering parts of the plant, not the stalks. Use gloves, as the dried flowers are a bit prickly. If your tub is overly full with dried plant material, split it into multiple buckets to prevent unintentional seed loss. Remove as much of the large plant stalk as you mash up the dried flowering material. The flowers do not need to be pulverized to dust - most of the seed is already dislodged through gentle agitation. Imagine ending with a slightly finer texture than what you started with - again, just whatever removes the flowers from the stalks! You’ll eventually be left with a mixture of ground flowers and lots of seeds. Here a fine mesh screen (anywhere from 0.45 to 0.075 inches) will facilitate the removal of additional flower chaff. While you may not have immediate access to such a screen, it’s inexpensive to source, easy to construct, and imminently useful for future seed saving projects or drying herbs. Any wood type will work to a build a frame, and sources such as McMaster-Carr or Darby Wire both carry screen material at the right gauge.

A box fan is essential for cleaning larger quantities of amaranth seed or if you desire eating quality grain. (dried flower stalks aren’t very tasty, so the cleaner the seed, the better the meal!). It provides a persistent dense column of air and removes small pieces of chaff that would otherwise be laborious to remove by hand. Gently pour the threshed and screened amaranth in front of a box fan, with an additional tub directly underneath. Play with fan speeds to prevent substantial seed loss. Find a happy medium between clean seed, partial seed loss, and maximal debris removal. You won’t save 100% of everything. That’s okay. Go for a critical mass of clean seed and know that “waste” will be enjoyed by birds or reseed the following year.

Our Varieties

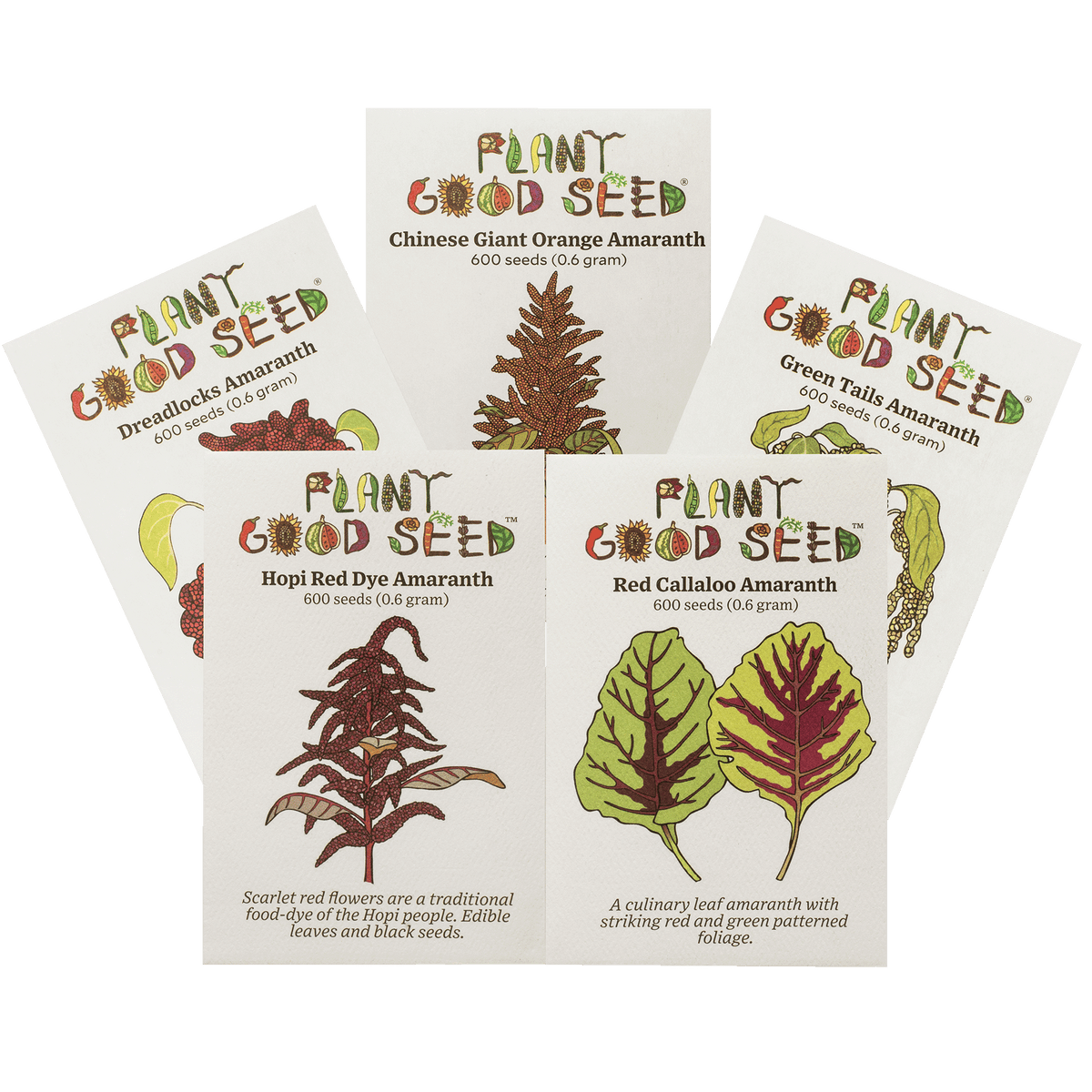

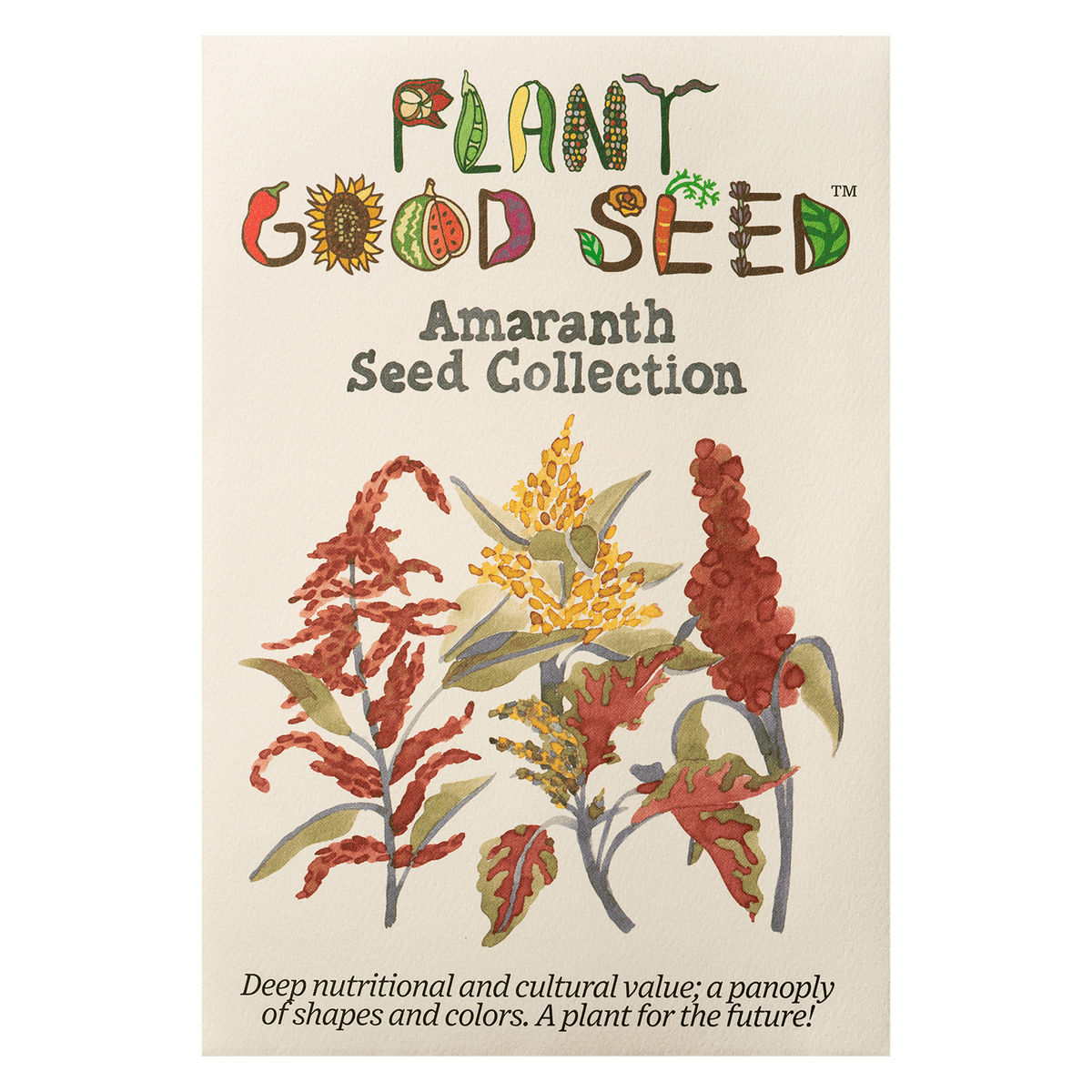

Historical agronomists Charles S. Kauffman and Leon E. Weber observed “no clear dividing line between a "grain" type and a "vegetable" type” of amaranth species.” I would add the same goes for the “cut flower” type. While there are implied use cases for each strain, all species can ultimately be used interchangeably. The caudatus species is primarily grown for cut flowers: Dreadlocks and Green Tails are two strains we carry. Hopi Red Dye is a bit of a crossover variety: its draping, tassily flower habit gives it bouquet potential, but as the name implies, it’s also used as a food dye and eating crop by the indigenous tribe. It’s the one I’ve produced here for grain eating at my house, as it seems the most weedy, self-reseeding year over year. Red Callaloo is the short king: ideal for leaf production, but stout growth and smaller flower heads means lower seed yield. Chinese Giant Orange is the workhorse variety grain production of the bunch: tall growth habit and seed yields of over a pound per plant. All species have different leaf patterning and colors, including seeds Green Tails and Chinese Giant Orange produce tan seeds while the others are black or luminescent dark red.

We also have three and five variety collection packets that presently (although may not always!) compose the entirety of our amaranth selections.

Bibliography

Brown, Dean. “Qualifying Dynamic Accumulators: A Sub-Group of the Hyperaccumulators.” Permaculture News, 12 May 2015. Archived 16 May 2024. Permaculture News (archived)

Brown, H. Claire. “Attack of the Superweeds: Herbicides are losing the war — and agriculture might never be the same again.” The New York Times, 4 May 2010. The New York Times

Gill, Nicholas. “The Story of Amaranth in the Americas.” New Worlder (Substack), 4 Mar. 2022. New Worlder

Hill, Nicole Patrice, and Kollibri terre Sonnenblume. “The Troubles of ‘Invasive’ Plants — zine.” Macska Moksha Press, 16 Jan. 2019. Macska Moksha Press

Heap, Ian. “The International Herbicide-Resistant Weed Database.” WeedScience.org, International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds, online database, 6 Jan. 2026. WeedScience.org

Kauffman, Charles S., and Leon E. Weber. “Grain Amaranths (Amaranthus spp.).” NewCROP: Proceedings of the 1990 New Crops Conference, Purdue University, 1990. Purdue NewCROP

Nowell, Cecilia. “‘It could feed the world’: amaranth, a health trend 8,000 years old that survived colonization.” The Guardian, 6 Aug. 2021. The Guardian

Tyler, Ben, and Greta Zarro. “Dynamic Accumulator Database and USDA Analysis.” Unadilla Community Farm, Google Sheets database, last updated 19 Jan. 2023. Google Sheets database

University of Missouri Extension. “MU Weed Science Team Confirms Dicamba-Resistant Waterhemp.” University of Missouri Extension News, 17 Dec. 2025. University of Missouri Extension

![]() All images and written content were created by real humans without any use of generative AI.

All images and written content were created by real humans without any use of generative AI.